Pritzker Architecture Prize 2003 -Jern Utzon

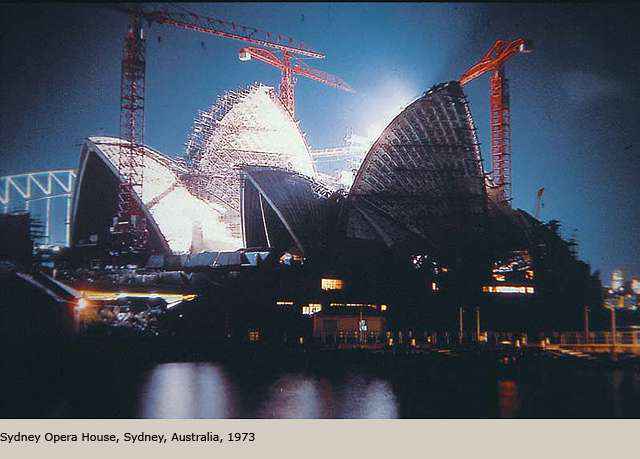

Jørn Utzon’s father was director of a shipyard in Alborg, Denmark, and was a brilliant naval architect, many of whose yacht designs are still in production today. Several family members were excellent yachtsmen, and the young Jørn, who was born in 1918, became a good sailor himself. Until about the age of 18, he considered a career as a naval officer. It was about this time, while still in secondary school, that he began helping his father at the shipyard, studying new designs, drawing up plans and making models. This activity opened another possibility—that of training to be a naval architect like his father. However, yet further influences were introduced during summer holidays with his grandparents. There he met two artists, Paul Schrøder and Carl Kyberg, who introduced him to art. One of his father’s cousins, Einar Utzon-Frank, who was a sculptor as well as a professor at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, provided additional inspiration. Jørn took an interest in sculpting. At one point, he indicated he might want to be an artist, but was ultimately convinced that architectural school would be the best career path. Even though his final marks in secondary school, particularly mathematics, were poor, his excellent freehand drawing talents were strong enough to win his admission to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen. He was soon recognized as having extraordinary architectural gifts. When he graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in 1942, because of World War II, he, like many architects of that time, fled to neutral Sweden where he was employed in the Stockholm office of Hakon Ahlberg for the duration of the war. Following that he went to Finland to work with Alvar Aalto. He had begun to admire the ideas of Gunnar Asplund, as well as Frank Lloyd Wright while still in school. Utzon acknowledges that Aalto, Asplund and Wright were all major influences. Over the next decade, he traveled extensively, visiting Morocco, Mexico, the United States, China, Japan, India, and Australia, the latter destined to become a major factor in his life. All of the trips had significance, and Utzon himself describes the importance of just one: “As an architectonic element, the platform is fascinating. I lost my heart to it on a trip to Mexico in 1949, where I found a rich variety of both size and idea, and where many platforms stand alone, surrounded by nothing but untouched nature. All the platforms in Mexico are placed very sensitively in the landscape, always the creations of a brilliant idea. They radiate a huge force. You feel the firm ground beneath you, as when standing on a great cliff. Let me give you an example of the power in this idea. Yucatan is a flat lowland area covered by an impenetrable jungle which everywhere attains a certain height. The Maya people used to live in this jungle in villages surrounded by small cultivated clearings. On all sides, and also above, there was the hot, humid, green jungle. No great views, no vertical movements. But by building up the platform on a level with the roof of the jungle, these people had suddenly conquered a new dimension that was a worthy place for the worship of their gods. They built their temples on these high platforms, which can be as much as a hundred metres long. From here, they had the sky, the clouds and the breeze, and suddenly the roof of the jungle was transformed into a great, open plain. By means of this architectonic device they had completely transformed the landscape and presented their eyes with a grandeur that corresponded to the grandeur of their gods. The wonderful experience of going from the denseness of the jungle to the vast openness above the platform is still there today. It is like the liberation you feel up here in the Nordic lands when, after weeks of rain, cloud and darkness, you suddenly emerge into the sunlight again.” The idea of the platform would manifest itself in many of Utzon’s designs over the years, including that of the Sydney Opera House, where he described it as follows: “…the idea has been to let the platform cut through like a knife and separate primary and secondary functions completely. On top of the platform the spectators receive the completed work of art and beneath the platform every preparation for it takes place.” Utzon continued, “To express the platform and avoid destroying it is a very important thing, when you start building on top of it. A flat roof does not express the flatness of the platform … in the schemes for the Sydney Opera House … you can see the roofs, curved forms, hanging higher or lower over the plateau. The contrast of forms and the constantly changing heights between these two elements result in spaces of great architectural force made possible by the modern structural approach to concrete construction, which has given so many beautiful tools into the hands of the architect.” The saga of the opera house actually began in 1957, when, at the age of 38, Jørn Utzon was still a relatively unknown architect with a practice in Denmark near where Shakespeare had located Hamlet’s castle. He was living in a small seaside town with his wife and three childen—one son, Kim, born that year; another son Jan, born in 1944, and a daughter, Lin, born in 1946—all three would follow in their father’s footsteps and become architects. Their home was a house in Hellebæk that he had built just five years before, one of the few designs that he had actually realized since opening his studio in 1945. He had just entered an anonymous competition for an opera house to be built in Australia on a point of land jutting into Sydney harbor. Out of some 230 entries from over thirty countries, his concept was selected—described by the media at the time as “three shell-like concrete vaults covered with white tiles.” It has become the most famous, certainly the most photographed, building of the 20th century. It is now hailed as a masterpiece—Jørn Utzon’s masterpiece. The Sydney Opera House is actually a complex of theatres and halls all linked together beneath its famous shells. Since its opening in 1973, it has become the busiest performing arts centre in the world, averaging some 3000 events a year with audiences totaling some two million, operating 24 hours a day, seven days a week closing only on Christmas and Good Friday. Books have been written, and films made chronicling the sixteen years it took to complete the Sydney Opera House. One such book is by Françoise Fromonot, Jørn Utzon – The Sydney Opera House. Utzon, who is described as being an intensely private person was unwittingly entangled in political intrigues and besieged by a hostile press, which eventually forced him out of the project before it was completed. But he was able to accomplish the basic structure, leaving just the interiors to be finished by others. As Pritzker Laureate and Juror Frank Gehry puts it, “Utzon made a building well ahead of its time, far ahead of available technology, and he persevered through extraordinary malicious publicity and negative criticism to build a building that changed the image of an entire country. It is the first time in our lifetime that an epic piece of architecture has gained such universal presence.” In the last year, plans were announced to refurbish the interiors, and Utzon, now 84, has high hopes that the interior will be full of color rather than a black hole. His son Jan is part of the new design team as Jørn Utzon’s representative. Their firm, Utzon Architects, has an agreement with the Sydney Opera House Trust and indirectly with the Australian government to work toward future development and renovation of the building. One aspect is to develop a Design Principles document, which will take a reader through the building explaining the underlying principles for the design decisions that produced the end results. The document will serve as a manual or guideline for future generations when alterations or modifications to the building are contemplated. Another aspect is to provide actual designs for a number of changes and modifications which are presently needed if the building is to comply to today’s expectations. Current work is concentrating on some of the interior spaces and access to the western foyer from the western boardwalk. Jørn Utzon has stated recently, “It is my hope that the building shall be a lively and ever-changing venue for the arts. Future generations should have the freedom to develop the building to contemporary use.”

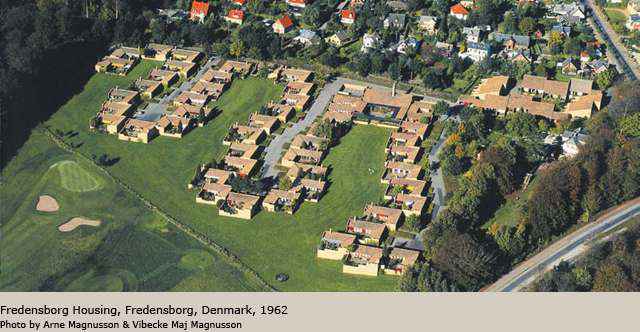

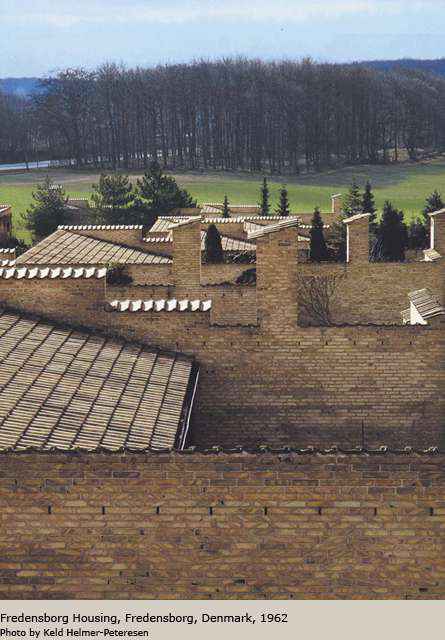

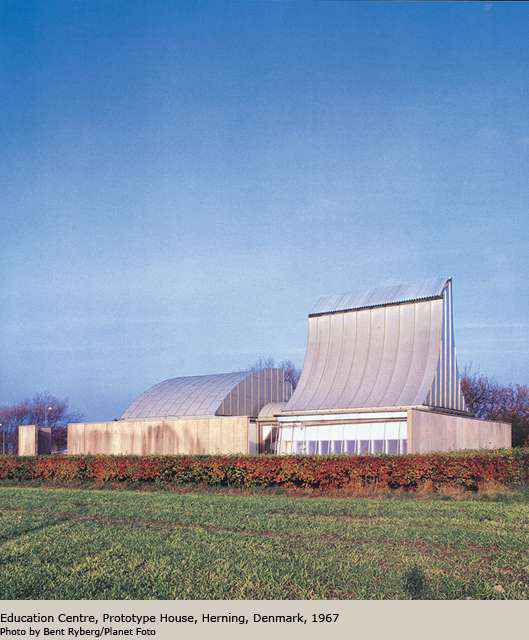

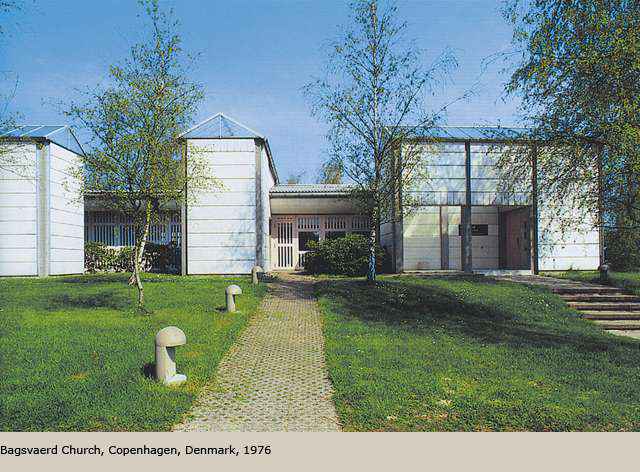

But Jørn Utzon has contributed far more than one masterpiece in his lifetime. As noted architectural author and critic Ada Louise Huxtable points out in her Pritzker Jury comments, “In a forty year practice, each commission displays a continuing development of ideas both subtle and bold, true to the teaching of early pioneers of a ‘new’ architecture, but that cohere in a prescient way, most visible now, to push the boundaries of architecture toward the present. This has produced a range of work from the sculptural abstraction of the Sydney Opera House that foreshadowed the avant garde expression of our time, and is widely considered to be the most notable monument of the 20th century, to handsome, humane housing and a church that remains a masterwork today.” She refers to the Utzon’s church in Bagsværd, a community just north of Copenhagen, where in the 16th century, the King of Denmark allowed an exisiting church to be pulled down to provide bricks for the restoration of a building for the university. The town was without a church building for 400 years, until their pastor happened to see some of Utzon’s work. “At an exhibition of my works, including the Sydney Opera House,” says Utzon, “there was also a drawing of a small church in the centre of a town. Two ministers representing a congregation that had been saving for 25 years to build a new church, saw it and asked me if I would be the architect for their church. There I stood, and was offered the finest task an architect can have—a magnificent time when it was the light from above that showed us the way.” The genesis of the design according to Utzon, went back to a time when he was teaching at the University of Hawaii where he spent time on the beaches. One evening, he was struck by the regular passage of clouds thinking they could be the basis for the ceiling of a church. His early sketches showed groups of people on the beach with clouds overhead. His sketches evolved with the people framed by columns on each side and billowing vaults above, and moving toward a cross. It’s not surprising that the end result provoked this comment from another Pritzker Juror, Carlos Jimenez who is an architect and teacher himself: “…each work startles with with its irrepressible creativity. How else to explain the lineage binding those indelible ceramic sails on the Tasmanian Sea, the fertile optimism of the housing at Fredensborg, or those sublime undulations of the ceilings at Bagsværd, to name just three of Utzon’s timeless works.” Both jurors Jimenez and Huxtable singled out “housing” in their comments. There are two courtyardstyle housing estates in Denmark designed by Jørn Utzon: the Kingo Houses in Helsingør and the houses in Fredensborg. His interest in courtyard-style housing was first shown in a competition for Skåne, Sweden in 1953. He based his designs on his own experiences. His family home in Ålborg had a nursery garden in front. The neighbors all had huts, sheds or some kind of shelters for a variety of activities—raising rabbits, boat-building, or simply storing items for family activities. Traditional Danish farmhouses had four sheltering sections set around a central courtyard. Further, Utzon had studied Chinese architecture which described their farm houses as being completely closed to the outside, but opening onto a central court. And he learned of a Turkish building regulation that allowed no one to block the view of existing houses. Designing with these tenets in mind, he won the Swedish competition, but the project was never realized. Not long after that, he took his Swedish plans to the Mayor of Helsingør along with a study he had done on a poorly designed and executed housing development that had been built in Denmark. He was able to convince the Mayor that he could provide his Swedish design for the same cost as the poorly done one. The Mayor put a tract of nine acres of land with a pond and rolling hills at his disposal for his housing plan. Utzon commissioned a show house from a firm of builders. The house was a success and eventually 63 houses were built within cost restrictions set up by the government to keep the costs below a certain level for low income workers. The 63 houses were built in rows following the undulations of the site, providing a specific view for each house, as well as the best situation possible for sunlight and shelter from the wind. Utzon likes to describe the arrangement of the houses as “like flowers on the branch of cherry tree, each turning toward the sun.” The individual houses are L-shaped with a living room and study in one section, and the kitchen, bedroom and bathroom in the other. Walls of varying heights closed the remaining open sides of the L. The success of these houses at Helsingør led to another for the Dansk Samvirke, a support organization for Danish citizens who have worked for long periods abroad in business or the Foreign Service. They wanted a development for retirees who had returned to Denmark and could live in a community and share their experiences. Utzon accepted the task of conceiving the program and designing the houses, even though no site had been found, and without fee if the project was not built. He helped find the site in Fredensborg, North Zealand, and developed a plan that allowed each house to have a view of and direct access to a green slope. Since there was no comparable society as this anywhere, Utzon had to invent the details of the project and make them conform to his idea for the individual houses. One of the things the committee wanted was a centre where the residents could meet, along with a dining room and kitchen, a communal lounge and party area. Some office space was needed as well as several guest rooms for the residents’ guests, which in effect became a small hotel. In the end, the Fredensborg development was designed with 47 courtyard and 30 terraced houses. The terraced houses were grouped around a square in staggered blocks of three, with all entrances from the square. A detailed account of this project is available in a book titled Jørn Utzon – Houses in Fredensborg by Tobias Faber with photographs by Jens Frederiksen. In addition to these projects in Denmark and Australia, Utzon has accomplished exceptional projects in Kuwait and Iran. In the former country, he designed the building to house the National Assembly. The invitation to compete for Kuwait National Assembly reached Utzon in 1969 while he was teaching at the University of Hawaii. There were few constraints to the project. The site was along the ocean front, with “haze and white light and an untidy town behind,” as Utzon describes it. As a result of his travels, Utzon had developed an affinity for Islamic architecture. In the definitive book by Richard Weston titled simply, Utzon, the project is described as follows: “The complex was conceived as an evolving fabric with, initially, ragged edges but of uniform height save for the representative spaces—the covered square, parliamentary chamber, large conference hall and mosque—which would rise as visually dominant group. These four major elements formed the corners of an incomplete but clearly implied rectangle, and the highest surfaces of their distinctive roofs—as specified in a three-dimensional sketch—were to lie in the same plane to create a ‘firm strong grouping’ to ‘hold the rest of the complex (which in its nature is irregular as it grows) together. Dominate it’ as Utzon explained in a note next to the sketch. The mosque was flat-roofed and anchored one corner of this spatial core—it would later be angled slightly toward Mecca—and its autonomy was stressed by making it independent of the office grid. The other roofs were sag curves, reflecting Utzons’s interest in fabric as a metaphor for concrete—we may recall it was shortly before this time that he had explored the Bagsværd Church’s cloud-vaults with fabric models.” It should be noted that in February of 1991, Iraqui troops, retreating before the international alliance, set fire to the building. Since, a 70 million dollar restoration was undertaken resulting in a number of departures from Utzon’s original design. Back in 1947 when Utzon was still a struggling young architect, a relative offered him an opportunity to supplement his meager income by going to work in Morocco preparing designs for factories there. The few months he spent there provided his first experience with Islamic architecture, which, just as the trip to Mexico had done, became another decisive influence on his work. In 1958, he was approached to design a branch of the Iran National Bank in the university area of Teheran. Utzon was delighted to take the job because of his intense interest in Islamic architecture. The client wanted the bank to stand out from its neighbors so, as described by Richard Weston in his book, Utzon, “Utzon decided to set it back on a raised platform framed by boldly projecting flank walls, thick enough to contain services. To one side the flank wall was doubled to form a servant zone to accommodate an office, private interview rooms and other support spaces; two additional administrative floors spanned between the outer walls above the entrance. The raised platform made for a dramatic entrance sequence: visitors pass through a low dark space, roofed by V-shaped beams, and then enter the open banking hall which expands dramatically both up and down, affording a sight of the whole interior.” In 1985, Utzon’s practice included his two sons, Jan and Kim. Ole Paustian, who headed one Denmark’s leading furniture companies, asked them to design a new showroom in a waterfront area of Copenhagen Harbor that would be an extension of one of Paustian’s existing warehouses. Utzon designed the showroom and an adjacent restaurant with sketches and sent them to his two sons who executed the final drawings and plans. Much later in 2000, Kim Utzon completed the complex with an adjacent office building and yacht club. Currently, Jørn Utzon lives in retirement with his wife Lis, on the island of Majorca, where they originally began building a home in 1971 and completed it two years later. It was almost twenty years later, that the Utzons decided to build another house on Majorca, nestled on the side of a mountain. The decision to build there was prompted by several reasons: the glare from the sea became very tiring for eyes weakened by a lifetime of close work with drawings; the pounding surf became more of a disturbance than a comfort; and there were more and more intrusions by architecture buffs seeking to wander the site. The design of Can Feliz, as the new home is named in a site called “Paradise,” harks back to Utzon’s love of the platform concept. The house has been described as a miniature acropolis. Jørn Utzon is an artist and architect whose response not only to ancient cultures of Islam and the Mayans, as well as the Japanese and Chinese, but also his affinity for nature, and the use of natural materials, places him in a firmament populated by only the most gifted of all the ages. One unrealized project bears mentioning here—the Silkeborg Museum of Fine Arts. A Danish artist named Asger Jørgensen (who later changed his name to Asger Jorn) approached Utzon in 1961 to build an addition to the Silkeborg Museum where a collection of his art work could be housed. He even volunteered to pay the architect’s fees because he could not see anyone other than Utzon designing the addition. The following is a portion of Utzon’s own description of the project, which provides a closer look at the architect’s thought processes: “The museum, which lies in an old, well-stocked garden with a wing divided into bays, is designed so that it does not disturb the surroundings, but concentrates 100% on the interior. “A building of several storeys above the ground would be like a bull in a china shop, and the respect for the existing calm wing of the museum calls for a solution that will not dominate the surroundings on account of its size. “It feels natural to bury the museum in the ground to a depth corresponding to the height of a threestoreyed building and only to allow the upper part—the roof lights taking up one storey—to appear above the ground level.“The design of this buried museum has a character rather like a cave or an oven. Because they are a direct continuation of the walls of the museum, the visible one-storey roof lights suggest this cave-like character and clearly demonstrate the reason for their special design. “In contrast to a square room, a cave has a distinct enclosed effect thanks to its natural shape without right angles. Continuous shapes such as we have in the museum express and emphasise the quadrilateral canvases and objects in the same powerful way that a cyclorama on a stage emphasises the individual characters and the flats. “The floor, too, has been included in this continuous movement, and these dramatic shapes also correspond well with the idea of digging the museum out underground. “The inspiration for the design of the museum comes from many different experiences -including my visit to the caves in Tatung, west of Peking, where hundreds of Buddha sculptures and other figures are carved in caves in the rocks by the bank of the river. These sculptures appear in all shapes in contrast to or in harmony with the surrounding space. The caves are all of varying sizes and shapes and with varying illumination. The old Chinese sculptors have experimented with all possibilities, and the most fantastic thing is a cave that is almost filled with a Buddha figure with c.7-metre-high face. Three platforms linked by ladders give the visitor the possibility of walking around and coming to close quarters with this gigantic figure. “Here, in this museum, it is possible to exhibit paintings and sculptures the size of a three-storeyed building so that it is possible to walk around the objects on all levels on the system of ramps, and perhaps the possibility of this kind of exhibition leads to a new line of development in decorative art in place of the ordinary form in public buildings today, which are merely easel paintings on a gigantic scale. “The various works of art can also be exhibited individually or in groups in every conceivable manner. It will also be possible in one of the large ovens to isolate a single large painting or sculpture that must be viewed on its own. “The continuous space in the museum provides surprising background effects with varied light for paintings and sculpture – a background effect of the same infinite character as a cyclorama on a stage. “The chimneys give the museum a clean, but varied roof light. The amount of light can be varied by means of blinds, and if it is so desired the roof light in the chimneys can be replaced with direct spotlight directed on a single object. The mullions supporting the roof lights are provided with suspension points so that they act like rigging loft in a theatre, so there will be the possibility of placing an object anywhere in the room. “The light mainly falls in along the walls and on the floors without disturbing shadow effects at the corners, and the irritation element from the direct light from above is avoided. “It will be with a sense of surprise and a desire to penetrate down into the building that the visitor for the first time sees the three-storeyed building open beneath him. Unconcerned – stairs and corridors which normally disturb – the viewer will glide almost effortlessly down into the museum via the ramp, taking him through the space. “Strict geometry will form the basis for a simple constructional shape. The visible curved external surfaces are to be clad with ceramics in strong colours so that the parts of the building emerge like shining ceramic sculptures, and inside the museum will be kept in white. “In the work with the curved shapes in the opera house, I have developed a great desire to go further with free architectural shapes, but at the same time to control the free shape with a geometry that makes it possible to construct the building from mass produced components. I am quite aware of the danger in the curved shapes in contrast to the relative safety of quadrilateral shapes. But the world of the curved form can give something that cannot ever be achieved by means of rectangular architecture. The hulls of ships, caves and sculpture demonstrate this.” While Jørn Utzon has retired with his wife to one of the houses he designed on Majorca, his sons, Jan who is 58 and has been working with his father since 1970, and Kim, who is 46, both carry on with Utzon Architects. A daughter, Lin, who is an artist of giant porcelain murals and other decorative media, works closely with architects. A third generation of Utzon’s, a son and daughter of Jan have both received their architecture degrees.