Sidewalk Labs, the architecture and urbanism arm of Google parent company Alphabet, has unveiled a digital model for what would be the world’s tallest mass-timber building, reaching 35 storeys.

Sidewalk Labs plans to build mass-timber high-rises as part of its redevelopment of the Toronto waterfront, but the current tallest buildings of this type are 18 storeys, and the company wants to go higher.

To explore how this could be achieved, the company spent a year working on “a digital proof of concept” or “proto-model” for a 35-storey timber high-rise, which would make it the tallest in the world.

It consulted a number of companies on the project, including architecture firms Gensler and Michael Green Architecture, which produced the visuals.

Summarised in a series of Medium posts, the project both provides insights into the building’s hypothetical performance and explores how it could be most efficiently built in parts at a factory.

Sidewalk Labs calls the proof of concept the team developed Proto-Model X (or PMX for short). Apart from its sustainable credentials, timber is attracting interest because it opens the door to a new age of affordable, efficient and low-waste construction, with parts cut in a factory and assembled on site.

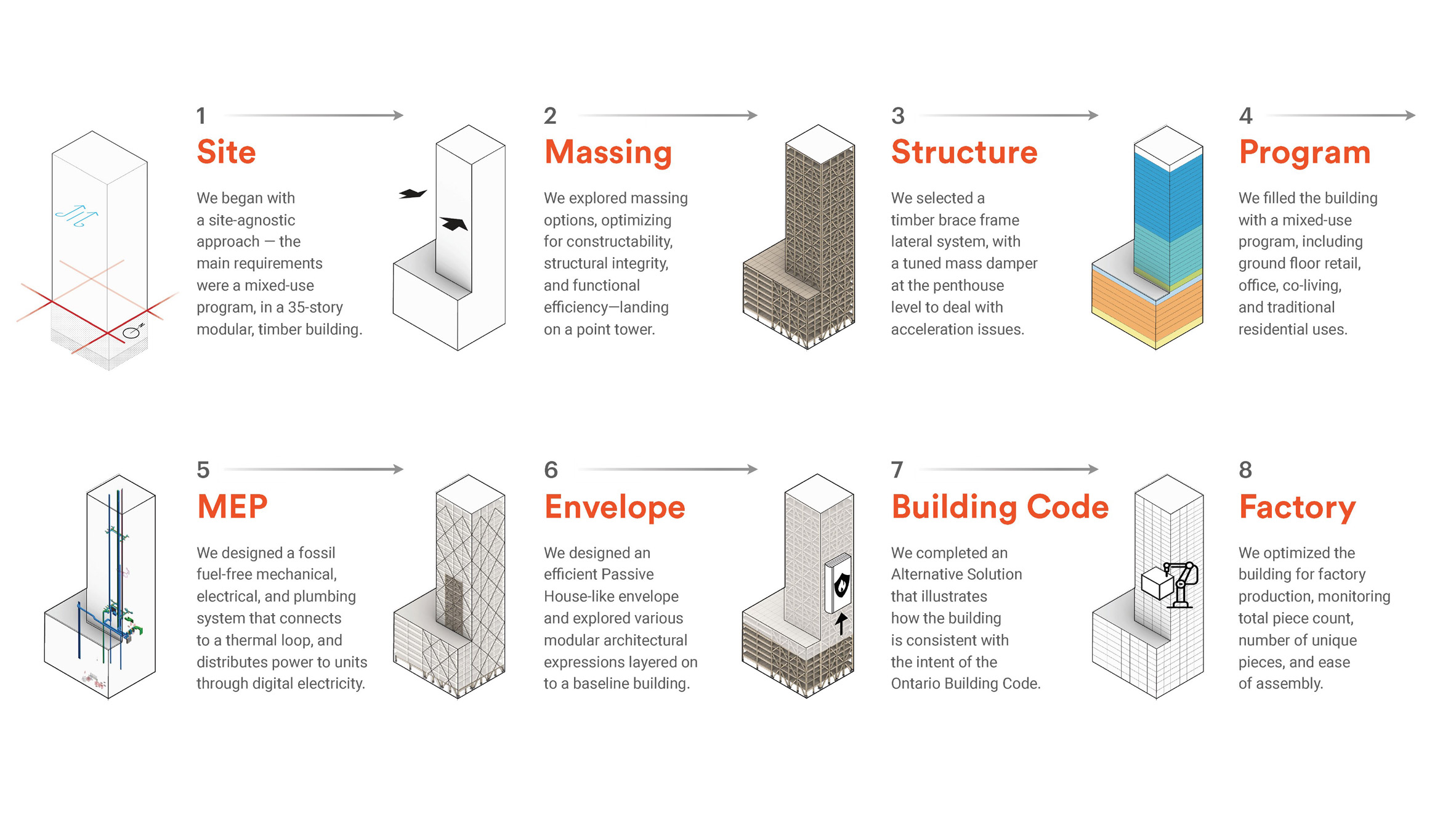

Sidewalk Labs rendered their mass-timber 3D building model in Autodesk’s Revit building software. The process involved eight distinct design steps, starting by exploring massing options and going on to plan a fossil-fuel-free mechanical, electrical and plumbing (MEP) system and create a variety of cladding.

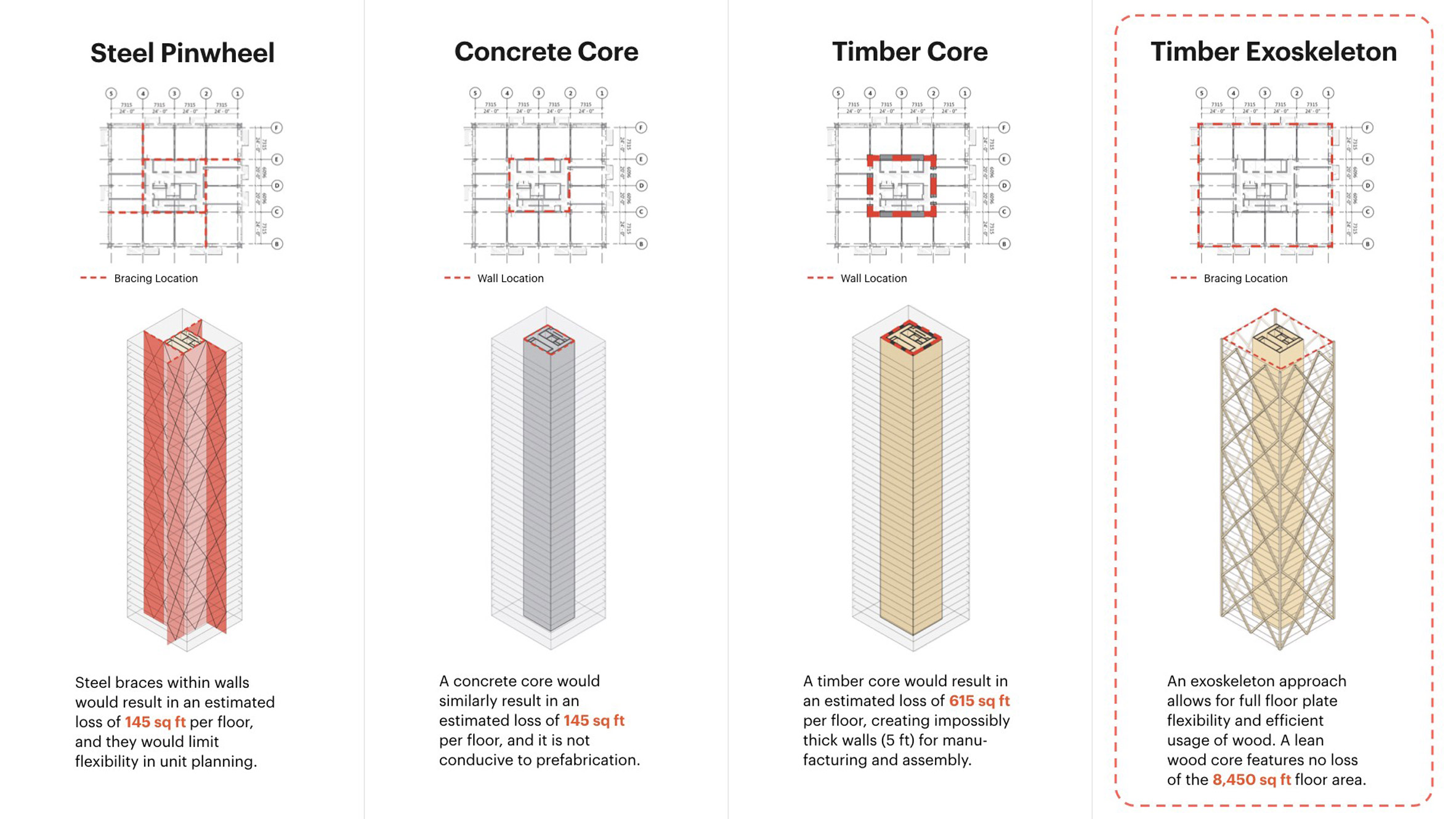

A key process was evaluating structural options. Because timber is lighter than other structural building materials — PMX is approximately 2.5 times lighter than its concrete equivalent — it is susceptible to lateral forces, like wind.

The team ruled out using a structural timber core, which would have had to be so thick it would eat into valuable floor space and be almost impossible to fabricate.

“That’s one of the reasons why many of the tall timber buildings completed to date are actually hybrids, reinforced at their cores by concrete walls or steel bracing,” writes project head Cara Eckholm in one blog.

“We preferred to work exclusively with timber, if possible, to capture its sustainability benefits and to prove the potential for manufacturing.”

Instead, the team “drew from engineering tactics more typical of super-tall building design”, using a cross-brace frame as an exoskeleton and a tuned mass damper to counter lateral forces.

The tuned mass damper is a 70-tonne chunk of steel connected by springs to the top of the building that provides a countervailing force to the sway from wind or earthquakes. It enables Sidewalk Labs to avoid the more environmentally unfriendly option of pouring concrete into the building core.

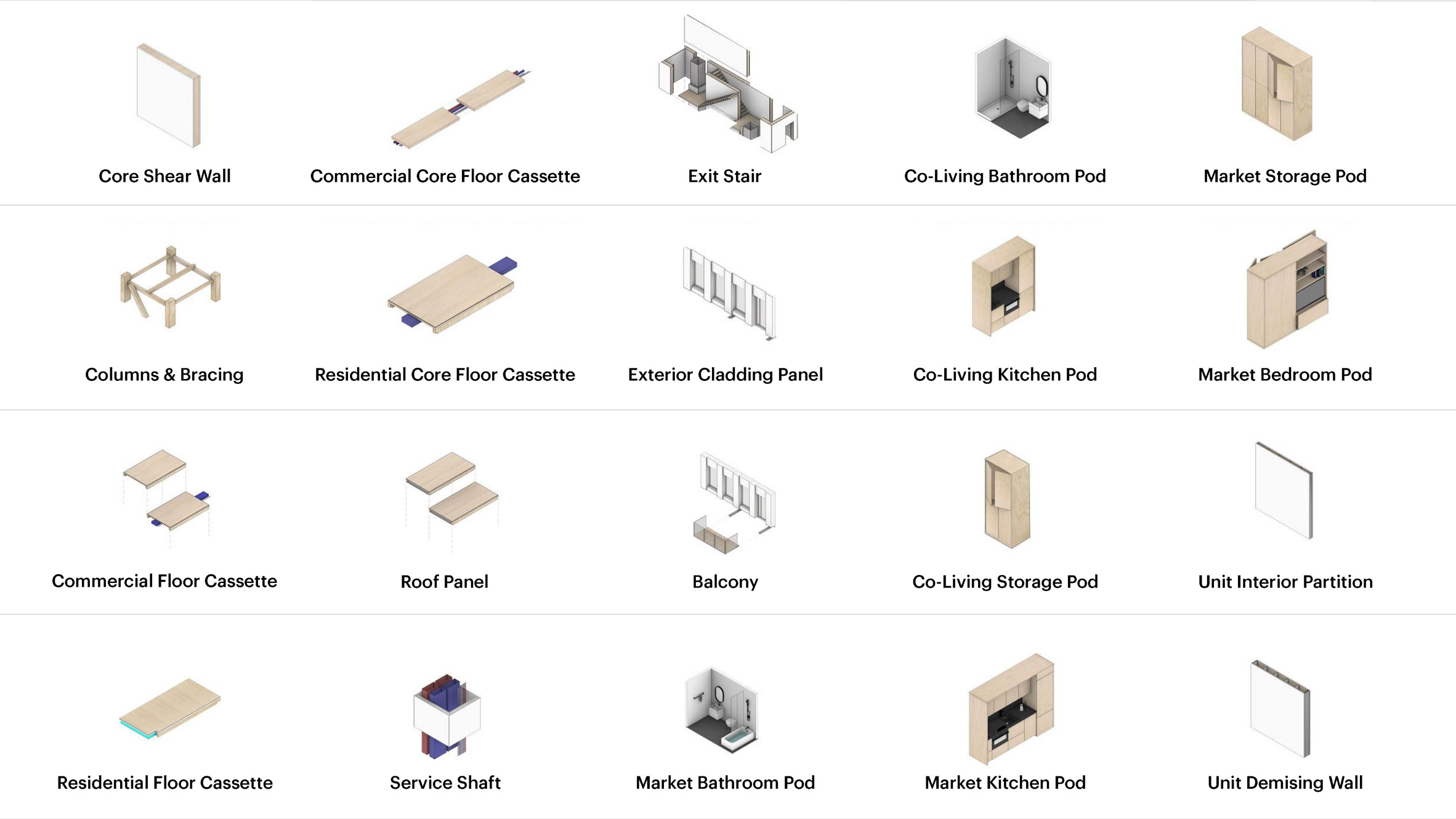

In a second blog, Eckholm looks at the final stages of Sidewalk Labs’ design process, where they examined how the building would be optimised for factory production.

Here, they worked to control the total piece count and number of unique pieces, and to ensure ease of assembly.

All of Sidewalk Labs’ mass-timber buildings would be produced from a “kit of parts” that is modular and interlocking.

This includes elements like balconies, walls, bathroom pods and kitchen pods, plumbing included. But its most basic unit is the “floor cassette” — a panel with acoustic and insulating layers that would be manufactured in 25 minutes on the assembly line.

“Using cassettes to construct floors is very different from how floors of high-rise buildings are constructed today,” Eckholm wrote. “In a typical site-built building, steel or plywood scaffolding is constructed to form the basis of the floor, with concrete poured on top — a long, arduous, and carbon-intensive process.

“Even in prefabricated buildings, which are few and far between, floor pieces are usually just basic concrete slabs, and the mechanical, electrical, and plumbing equipment has to be secured in place separately,” Eckholm added.

Finally, the team looked at cladding, designing a number of “skins” for the building envelope to avoid creating a cookie-cutter landscape of identical facades. Their options include a diamond pattern, coloured shutters and a faceted effect.

“With construction costs booming in many major cities, timber is one potential solution for delivering more affordability. But instead of leading to generic high-rises, timber buildings can form dynamic neighbourhoods celebrated for their distinct architecture — not just their efficient engineering,” concludes Eckholm.

Sidewalk Labs won the bid to develop the Toronto waterfront, on the Lake Ontario shoreline, in 2017, and has been working on it ever since.

Other aims for the experimental scheme include proposals for Building Raincoats, wayfinding beacons and heated pavements.

Its proposals for a high-tech smart city have drawn some criticism, however, with concerns about surveillance and data collection leading to new restrictions on the project as of late 2019.

The post Sidewalk Labs tests possibilities for timber construction with 35-storey “Proto-Model” appeared first on Dezeen.